Entering Folsom State Prison, Henry Thurman looked over his shoulder only to see the steel door click decisively shut behind him.

One of the more imposing incarcerated men, both in size and reputation, approached Thurman’s group.

“I understand one of you is a teacher,” the menacing-looking figure said. “Which one is it?”

The truth is that Thurman is indeed a teacher, a mentor and a leadership counselor, which is why he was visiting one of the most notorious lockups in the country. Yet he was hesitant to answer.

Finally, Thurman managed a quiet “Yes, I am a teacher.” After a few seconds of silence, which probably seemed a lot longer, the man softened.

“I got a message for you,” he said, directly addressing Thurman. “I’m in here because of some mistakes I made, some bad choices. You’ve got a chance with these kids so they can do better.

“When you go back, I want you to make sure that happens for these kids as best you can.”

And for 45 years, Kenosha Unified teacher Henry Thurman has done just that. Through changes in education, technology and the community, Thurman has given his students his best.

At the end of this school year, “Mr. T” will close the door to his energetic, diverse, loud, loving classroom at Brass Community School for the last time, and head into his well-deserved retirement.

“The kids have been my mentors,” Thurman said. “Working with indigenous folks I learned just to follow and trust spirit, and that’s what I got from these kids. Especially in kindergarten.

“We have the lesson plans and all that, but these kids have another plan, another scheme. I found out I got a lot more mileage by following their scheme. We stay within the protocol, but I’m able to hear what they are saying.”

It says a lot about Thurman that even at age 66 with a four-and-a-half decade career behind him, when he announced his retirement at a recent staff meeting many colleagues were surprised. There were even tears.

The outpouring of affection is evidence that Thurman’s teaching philosophy reached not only kids, but grown-ups alike.

“You can come with all the books and all the knowledge and all the theories and whatnot, and that’s good,” he said. “But the students don’t care what you know, they want to know that you care.”

To say Thurman is an anomaly is an understatement.

Thurman spent his entire career in only two schools, moving only because Lincoln and Durkee merged to form the new Brass Community School, his home since it opened in 2008. He’s a male teaching kindergarten, although he certainly didn’t start out there. He went to Carthage College on a full scholarship, and was a collegiate tennis player and even a local club pro, two outcomes that were not typical in the Milwaukee neighborhood where he grew up. He’s lived in only two cities 30 miles apart, yet he’s traveled the world, teaching everywhere he goes.

Those things all happened either because someone saw something special in him, or he saw something special in an unusual situation.

Take for example, his tennis career. He played at Milwaukee Rufus King High School and Carthage College, then became an assistant to Kenosha coaching legend Harry Stoebe at the Towne Club. Thurman eventually became both the boys and girls coach at Tremper High School.

That all started when he and a buddy found some tennis balls in the street on their way to track practice, and whipped them back over the fence at the request of the tennis coach running a practice there.

“After a couple days of that, the coach said, ‘Hey, why don’t you come try tennis,’” Thurman recalled. “I told him I didn’t want to play a chump sport, it was too easy.”

The coach challenged the kids to try to volley the ball back and forth, and if the boys could prove tennis was too easy for them, he’d stop asking.

“We had balls flying over the fence, every which way,” he said, remembering the humbling experience. “The next day we came and tried again, and this time we stayed.”

“Getting to work with Henry at Brass has been a blessing for me in many ways.”

– Joel Kaufmann, Brass Community School principal

In fact, responding to a challenge is how Thurman landed in kindergarten.

In 1998, when Thurman was in his 20th year of teaching sixth grade, KUSD transitioned to the middle school model, bringing sixth grade into the middle schools and freshmen into high school.

“I was all set up to teach in a house at Lincoln in sixth grade. But something didn’t sit right. I’d gone to the first couple meetings, but it wasn’t jibing with me for some reason,” he said. “Then (administrators) asked me how I’d like to be a dean, I looked into it but decided I didn’t want to do that. They told me if I didn’t want to be dean, the only thing they had left for me was first grade or kindergarten.

To everyone’s surprise, and to the tremendous benefit of the next 25 years of 5- and 6-year-olds, Mr. T said, “Bring it on” and was assigned to a first grade class, quickly followed by kindergarten.

Then it was his turn to be surprised.

“When I went to first grade, I saw a big gap between sixth grade and first grade,” Thurman said. “But the gap between first grade and kindergarten was a heck of a lot bigger.

“I was not ready for that. Tying shoes and going to the bathroom and all that, it was a different world.

“I don’t know how many times that summer I saw ‘Kindergarten Cop.’ ”

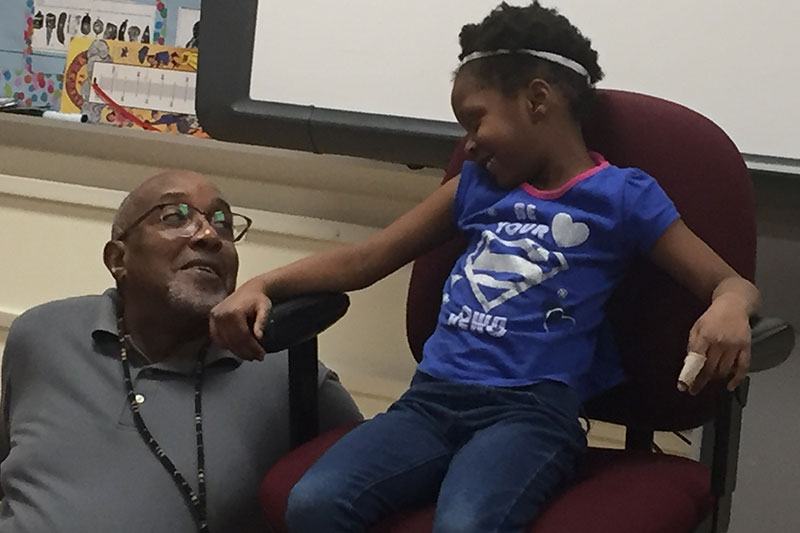

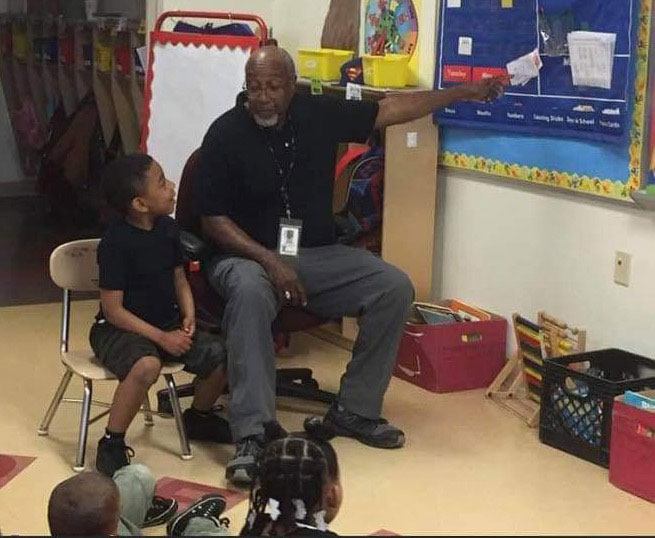

As it turns out, Henry is a big kid at heart, and that heart really did belong in kindergarten. If he felt trepidation about those soggy shoelaces and runny noses, he kept it to himself. From Day 1, every child who entered Mr. Thurman’s class knew they belonged. They even had a name: “The Thurmanators.”

“It just fell into place,” he said. “Maybe it was my personality, by allowing the kids to be themselves immediately there was this trust, and the relationship was bonded. When I sang, regardless of how it sounded, they would sing and dance and do whatever. The teaching flowed out of that.

Thurman added: “My big thing is that I’ve always wanted to be included. I saw a world where there was no fence, no barriers. This was about inclusiveness. When you teach the way we do in this classroom, we want everyone to be respected. We want the kids to have a sense of knowing who they are and where they came from, something about their lineage and heritage. That’s the multicultural piece.”

Thurman said that he believes families could sense that inclusiveness, perhaps a vibe that he was a safe person they could come and talk to and trust. Former students came in droves year after year just to keep in touch as well.

That “vibe” was always apparent during Brass’ traditional front porch visits to every family before the first day of school. All ages would come out to greet “Mr. T,” many asking, “Do you remember me?” He always does.

Parent Diana Harris recalled how Thurman was able to get her son Damani to participate, something that had previously proved challenging.

“I don’t know if the kids realize it or not, but the kids are just so lucky. It’s a huge loss to our district for sure.”

– Scott Kennow, former Brass Community School principal and current Indian Trail High School principal

“He would let Damani ‘teach’ to get him engaged with his peers, that meant so much,” she said. “Most of all I want people to know that Mr. Thurman never gave up on my son. I couldn’t be more grateful and so honored to have him teach my son.”

Even when Thurman moved back to Milwaukee to care for his ailing parents, his career never left the Uptown/Lincoln Park neighborhood, He taught, coached, ran open gym, and even started a wrestling program at Brass with longtime KUSD coach and art teacher Jerril Grover. He has another strong connection to the district as his daughter, Denee Frazier, is a longtime substitute who has been known to bring her enthusiasm to her dad’s classroom on occasion.

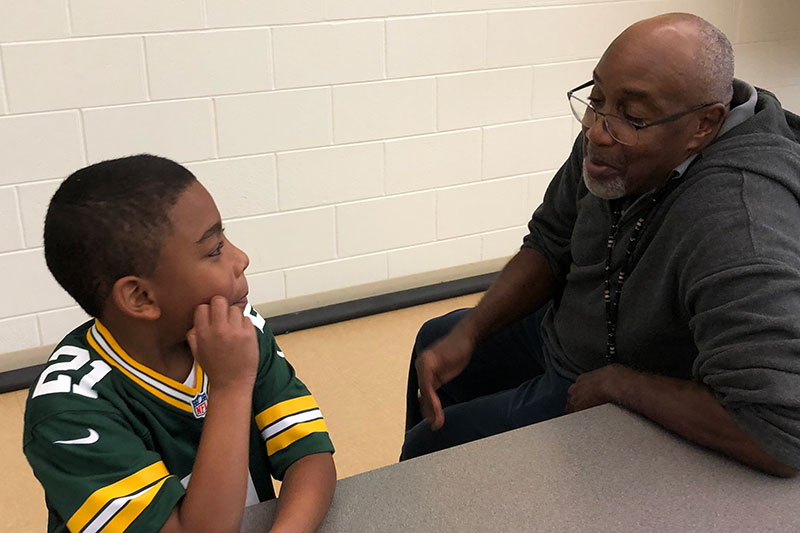

Thurman has been a stable presence at the school and in the neighborhood through more administrators than he can count. His two most recent bosses, current Brass principal Joel Kaufmann and Scott Kennow, shared the sentiment that Henry taught them more than they taught him.

“Getting to work with Henry at Brass has been a blessing for me in many ways,” said Kaufmann, now in his sixth year as BCS principal. “His calm demeanor and care for his students and the staff at Brass can be felt every day.

“The impact Henry has had on me as an educator has less to do with the classroom and more to do with me knowing that whenever I need to square myself with a situation, I can always walk into room 110 and know that ‘Mr. T’ will lend his ear and his wisdom to whatever is going on.”

Kennow was Brass principal from 2010-2015, including when Thurman was named KUSD Teacher of the Year in 2014. Now the principal of Indian Trail High School, Kennow said Thurman remains a huge influence on his career.

“For me, when you’re in a leadership position, the best people to talk to are the ones that you’re serving, and the ones who serve others,” Kennow said. “As I got to know him, I saw that Henry does so much leadership not only within our community but globally. We’d talk about different cultures that he’s visited, and his stories and experiences. I look at him as just a tremendous resource for me as a leader to get a perspective. I definitely appreciated it. Anytime he told me ‘Scott, I appreciate you,’ I told him it’s ten-fold in return.

“It’s hard enough being a kindergarten teacher, to find a male to do it is nearly impossible, to find a Black male to do it is hitting the jackpot. Those kids look up and see someone who looks like them, who is going to be that caring, it’s just amazing. I don’t know if the kids realize it or not, but the kids are just so lucky. It’s a huge loss to our district for sure.”

KUSD Superintendent Dr. Sue Savaglio-Jarvis also paid tribute: “Mr. Thurman is a steadfast, dedicated and committed educator who for 45 years gave his life tirelessly to the students and staff he served. His contagious smile and warm heart will be dearly missed but always remembered.”

Another way Thurman’s career has touched so many lives is his willingness to take on challenges and turn them into, as he would put it, an “even better still” situation.

At just 21, Thurman graduated from Carthage College with a double major in elementary education and special education. Offered his choice of either job, Thurman settled on traditional classroom teaching. While that meant scores of children with special needs wouldn’t receive his direct counsel, Thurman remedied that by taking on several unique challenges.

For nearly 35 years Thurman served as a coach, chaperone and board member of the Special Olympics. His involvement included tennis, basketball and even bowling, and ranged from local to national events and even the World Games, where he was named head coach for both basketball and tennis. The real reward, however, came from the athletes.

“They accept you for who you are,” Thurman said of the Special Olympians. “They taught me they don’t have any barriers. When they were called disabled or handicapped, they would tell me, ‘No we’re not handicapped, we just do things differently.’ ”

Thurman’s respect for children with special needs, their families and special education teachers made him the “go-to” classroom as KUSD moved toward an inclusion model.

That means that after flying solo for decades, Thurman eventually found himself co-teaching within the same classroom with a special education teacher and support staff. These colleagues (including one who upon learning of his retirement plans decided to retire herself) refer to their co-teaching experience as the best years of their career. They saw their students being truly accepted, loved, and recognized for the leadership in their unique abilities.

“I learned from one of my colleagues that every child has special needs,” Thurman said, “and every child is gifted.”

“When you teach the way we do in this classroom, we want everyone to be respected.”

– Henry Thurman, retiring Brass Community School kindergarten teacher

Also part of Thuman’s connection to people with unique abilities is his work with the deaf community. Thurman has American Sign Language skills he shares with his classes, and was part of the Kenosha Sign Singers. Like so many other of his endeavors, he found his way there through KUSD colleagues.

What’s next? Thurman’s work with the Mankind Project has already taken him around the world, teaching workshops in South Africa, various parts of Europe and Canada and well as throughout the United States from the biggest cities to South Dakota’s Pine Ridge Reservation.

Thurman has taken on a leadership role with the international organization whose stated goal is to “empower men to missions of service, supporting men to make a difference in the lives of others around the world. Mankind Project is likely the next chapter of his life’s work, and the source of his personal mission statement:

“Through God’s grace and divine love, I create a global village by living and blessing diversity.”

In considering the end of his storied career, Thurman is realistic about just how much things have changed. Revisiting some of his favorite memories invoked sadness, as things like taking the safety patrols tobogganing, chaperoning trips to Phantom Ranch, and planning enriching field trips and assemblies are just memories, pushed aside to make room for more assessments, more scripted curriculum.

Even so, until now Mr. Thurman wasn’t ready to hang it up.

“In my heart of hearts, I just wasn’t ready until now,” Thurman said. “I talked about it for a couple years. But as a friend said, Little Henry was not ready to leave. Big Henry will know when Little Henry is ready to go, and then they’ll both be happy.”